Andean Cosmology

©1998 by James Q. Jacobs

Ethnohistorical records have provided information about Andean cosmogonic beliefs at the time of European contact. These records reflect the pervasive ethnocentrism of the invading conquerors. They also provide the only written record available. What can be inferred today depends on scant and biased evidence. It is important to keep in mind that Spanish chroniclers were writing during inquisitional times when heretics were put to death. Even writers such as Garcilaso de la Vega, the illegitimate son of a Spanish conqueror and an Incan prince, although half-Incan, was reared a Catholic, became a minor cleric and wrote for an audience in Spain. In this article the word religion is used in its broadest sense, encompassing cosmogonic beliefs, world view, and practices and ceremonies reflective of these.

THE PREHISTORIC TRADITION

Inca religion combined features of animism and a respect for nature. The Sun, Moon, the cosmos, human progenitors, the highest mountains and such phenomena as lightning and thunder were venerated. The Inca pantheon was headed by Viracocha (the creator and a culture hero), Inti (the Sun), and Pacha Mama (the Earth Mother). Inca religion combined features of animism and a respect for nature. The Sun, Moon, the cosmos, human progenitors, the highest mountains and such phenomena as lightning and thunder were venerated. The Inca pantheon was headed by Viracocha (the creator and a culture hero), Inti (the Sun), and Pacha Mama (the Earth Mother).

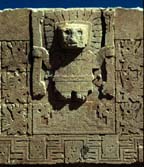

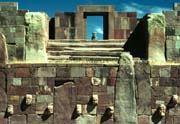

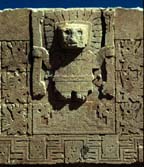

Viracocha was the creator of the Incas, the Sun, Mother Earth and all else. Viracocha was called señor del universo, señor del principio, señor de la primera causa, señor del fundamento, señor del origin, supreme founder, and Creator of all parts. Viracocha was also the creator of the Tiwanaku civilization, of which the Incas were cultural heirs. According to myth he was believed to have created the sun and moon on Lake Titicaca. After forming the celestial realm and the earth, Viracocha wandered the earth teaching people the arts of civilization. He was sometimes represented carrying a staff. It is likely that Viracocha is the figure sculptured on the Portal of the Sun at the megalithic ruins of Tiwanaku near Lake Titicaca in Bolivia.

Viracocha was the protector of Inca Pachacuti. He appeared to Pachacuti in a dream when Cuzco was under sieged by the Chanca tribe. Pachacuti defeated the Chanca, ascended to the position of Inca, and built the monument to Viracocha in Cuzco.

Inti, the Sun, was believed to be the ancestor of the Incas. Inti was usually represented in human form, his face portrayed as a gold disk from which rays and flames extended. Inti's sister and consort was the moon, Mama-Kilya, portrayed as a silver disk with human features. Inti was the most important member of the Inca pantheon. The Sun's powerful energy warms the earth, is vital to life and produces crops; and, as such, was of primary importance to the agrarian civilization. Inti was at the head of the state religion, and his veneration was proscribed throughout the Inca empire. The Incas viewed themselves as descendants of the Sun. The common people believed the Inca was in communication with Inti.

The belief in Pacha Mama encompasses the view that the Earth is a living being. The earth is also considered the mother of all earthly life, an outlook plausible from an empirical viewpoint and from a supernatural perspective. Pacha Mama (pacha means earth, mama means mother) is the personification of fertility and growth as well as the representation of the female aspect of the Earth, the mother of all life. The season of growth, the November to April rainy season, is associated with Pacha Mama. The dry season is associated with Pacha Tata (tata = father).

According to modern historian-author John Hemming,

"At the time of the Conquest, religion had been all-pervading in the Inca empire, but it flourished at different levels. At the top was the official religion, closely identified with the Inca himself. There was the worship of the sun, moon stars, thunder; of the creator god Viracocha; of the Inca as son of the sun; of the mummies and effigies of his royal ancestors, and the holy hills and caves of the Inca creation legends." (Hemming 307)

The Incas maintained a cast gold man-sized effigy called Punchao (meaning day, image of the sun). It was described by Viceroy Toledo as having "a heart of dough in a golden chalice inside the body of the idol, this dough being of a powder made from the hearts of dead Incas." (Hemming 318) This most important image of Inti was captured with Tupac Amaru and probably melted for its gold by Viceroy Toledo.

Diego Rodriguez de Figuero, first embassy of the Spanish in Vilcabamba, wrote a explicit report of his travel. He reported about solar veneration by Inca Titu Cusi and his captains. He noted diplomatic proceedings being interrupted for religious observances. Upon the ratification of the treaty of Acobamba, which ended the hostilities between the Spaniards and Vilcabamba for a short period, Titu Cusi is reported to have sworn facing the sun with upheld arms while incanting, "I swear to thee, O Sun, who art creator of all things and whom I hold to be God and worship; and by thee Earth, whom I regard as mother from whom is produced all sustenance for the support of man" (Temple in Hemming 319). Diego Rodriguez de Figuero, first embassy of the Spanish in Vilcabamba, wrote a explicit report of his travel. He reported about solar veneration by Inca Titu Cusi and his captains. He noted diplomatic proceedings being interrupted for religious observances. Upon the ratification of the treaty of Acobamba, which ended the hostilities between the Spaniards and Vilcabamba for a short period, Titu Cusi is reported to have sworn facing the sun with upheld arms while incanting, "I swear to thee, O Sun, who art creator of all things and whom I hold to be God and worship; and by thee Earth, whom I regard as mother from whom is produced all sustenance for the support of man" (Temple in Hemming 319).

ANCESTOR VENERATION

Ancestor veneration was a fundamental practice of Andean society. It was believed the deceased were active in maintaining the well-being of the living. Forbearers defined societal organization, with ayllus (kinship groups descended from a common ancestor) named for their founders.  Veneration extended to the ancestor or ancestors of a group, and to ancestral places of origin. Ancestor reverence included preservation of the deceased in mummified and other forms, such as the keeping of skulls of progenitors. The mummy might be richly clothed, brought out for major festivals and even attended at special facilities. Inca mummies were even included in important meetings. The ancestor mummies and images of mythical ancestors participated in ceremonies. Ciezo de León wrote that each Inca mummy had its own service set in gold and silver. At certain festivals, and particularly at a funeral for an Inca, the mummies of all the Inca's predecessors were brought out into the plaza in Cuzco and the eulogies of the lineage were chanted. These mythical ballads were relied upon by ethnohistorical writers and provide in part what we know today of the history of the Incas as they viewed it upon contact. Veneration extended to the ancestor or ancestors of a group, and to ancestral places of origin. Ancestor reverence included preservation of the deceased in mummified and other forms, such as the keeping of skulls of progenitors. The mummy might be richly clothed, brought out for major festivals and even attended at special facilities. Inca mummies were even included in important meetings. The ancestor mummies and images of mythical ancestors participated in ceremonies. Ciezo de León wrote that each Inca mummy had its own service set in gold and silver. At certain festivals, and particularly at a funeral for an Inca, the mummies of all the Inca's predecessors were brought out into the plaza in Cuzco and the eulogies of the lineage were chanted. These mythical ballads were relied upon by ethnohistorical writers and provide in part what we know today of the history of the Incas as they viewed it upon contact.

The bodily remains were called 'ylla,' meaning 'cuerpo de el que fue bueno en la vida' (body of one who was good in life), and 'yllapa,' meaning 'trueno o relánpage' (thunder or lightning). Guamán Poma de Ayala wrote that the Inca, upon dying, was transformed into 'illapa' (thunder). He also reported that the mummies participated in various ceremonies together with images of mythical ancestors. The solstical ceremonies were particularly dedicated to the mythical ancestors and remembrance of origins. Inti Raimi, the festival of winter solstice and the beginning of the year commemorated the myth of the appearance of the ancestors, of creation. The festival actualized the myth of origin and supported the perpetuation of the ancestral order.

HUACAS AND CEQUES

Hemming reports that during the Inca empire the huacas around Cuzco were arranged in lines called ceques. The Sun Temple in Cuzco, the Coricancha, was the sighting point for this system of irradiating lines to distant horizon features and mountains.  Along these forty-one ceques, extended to the horizon and beyond, were located 328 survey points or huacas. This number equals the number of days in 12 lunar orbits. Along these forty-one ceques, extended to the horizon and beyond, were located 328 survey points or huacas. This number equals the number of days in 12 lunar orbits.

Huacas are a general category of sites such as mountains, rocks, hills, springs, caves, made-made pyramids, pillars, towers, and other monuments, places of origin, burial places, caves of ancestors, cairns of stones and other special places in the landscape. One such monument is the Yurac-rumi (white stone) in the Vilcabamba valley, discovered by Hiram Bingham, discoverer of Machu Picchu.

The 25 by 52 feet white granite outcrop is covered with complex carvings, including rectangular seats, projecting stone squares, a cave with niches, a flattened top and platforms. Another class of carved bedrock stones are the Intihuatanis, the 'Hitching Posts of the Sun.' Intihuatanis were considered to be of importance, as inferred by the fact that those found were destroyed by the Spaniards. Symbolic offerings were left at huacas. At stone piles on mountain passes the passerby would add a stone to the cairn.

The Intihuatani at Machu Picchu. Machu Picchu and the Inca Trail Placemarks. INCAN RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS

Under the Inca empire there was a highly organized state religion. The official priesthood maintained temples and convents in the main cities. Priests resided at important shrines and temples. Near South America's highest peak, Mount Aconcagua in Argentina, near the southern extreme of the Inca realm, an ancient monument of high regard was maintained. On Titicaca Island in Lake Titicaca a House of the Sun and a House of the Moon were maintained. These two may have symbolized the creation of the Sun and the Moon by Viracocha, an event mythically linked to the lake, or may have been linked to ancestors of the Incas.

The most important Monument of the Incas was the Coricancha (Golden Enclosure) in Cuzco, wherein there was a room with models of plants, animals, birds, and even the clumps of earth, all of gold. The Coricancha House of the Sun was used by the royal family in important ceremonies such as winter solstice. A drawing of Incan cosmogony on the main altar of the Coricancha was created by the Indian chronicler Juan Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yanqui Salccamaygua. Roberto Lehmann-Nitsche wrote of the altar, "in its images they concentrated the most important manifestations of religious concepts from a specific period and a population that reached the highest development of aboriginal South American civilization." (Valencia, 90, my translation)

In Juan Santa Cruz's drawing in the top center a large oval form symbolizing Viracocha is flanked by the sun and the moon. Below the sun the earth is drawn, with Venus as Morning Star between them. Evening Star is shown below the moon. A rainbow is depicted over the earth, with lightning off to one side. In the lower center of the drawing are a man and a woman, considered to represent the the primordial couple. A scattering of constellations is also included, as is a tree and the ocean. Above the large ovoid area representing Viracocha stars thought to represent the equatorial constellation of Orion are depicted. The Southern Cross is drawn immediately below Viracocha. The ovoid Viracocha of Santa Cruz's drawing represents the Coricancha's ovoid golden image of Viracocha. The use of an ovoid form represents the understanding of Viracocha as a cosmic egg. The sun image in the Coricancha was also of gold and is mentioned in chronicles.

A portion of the produce of the people was taxed, and therefore supported the magnificent monuments and religious institutions maintained by the state. A portions of the land was also allotted to the Sun (in effect the state) and administered to support the temples, the priests and the chosen women, the ruling family and the state administration. State administrators and religious officials were of the same societal ranking and publicly supported. The rendering of service to the Sun/state was required of the populace, in the form of farming the state lands and caring for the herds on these public holdings. The state resources were redistributed in times of drought or calamity, enhancing community stability.

A priest's title was umu, meaning a curer. The title of the chief priest in Cuzco, who was of noble lineage, was Villac Umu. He held his position for life, was allowed to marry, and was parallel in authority with the Inca. He administered all shrines and temples and appointed priests. Convents were also known. Women were selected at a young age to join these separate communities that served the religious institutions and the leaders of the society. The Incan religious institutions and monuments were destroyed by the Spanish conquerors' campaign against the perceived idolatry. Under Incan administration previous religious practices and local customs had been tolerated to a greater extent. Some regional religious customs and sites were incorporated by the Incas. At Pachacamac, on the central coast of Perú, an Incan convent was built near the immense ancient pyramid. Upon contact the original, pre-Incan shrine was destroyed by the Spaniards.

FESTIVALS

Festivals followed the natural agricultural cycle and the rhythm of the seasons and included both religious and social aspects. Music and dance were an important component of festivals, as was drinking of inebriating beverages.  The most solemn festival of the four festivals that the Incas celebrated in Cuzco was the Inti Raimi, (described in detail in the linked page, part of this web ring) commemorating the passage of the winter solstice in June. The solstice festivals were the most important occasions of the year. The 30-day calendar was astronomically based, and each month had its own festival. The waxing and waning of the moon determined the monthly cycles and the times for Inca festivals. In his letter to Philip II, Guamán Poma de Ayala offered two different versions of Andean religion, one centering on state ceremonies at Cuzco and the other describing the agricultural practices at the local level. Different calendars prevailed on the irrigated coast, where the agricultural cycle has a different schedule. The most solemn festival of the four festivals that the Incas celebrated in Cuzco was the Inti Raimi, (described in detail in the linked page, part of this web ring) commemorating the passage of the winter solstice in June. The solstice festivals were the most important occasions of the year. The 30-day calendar was astronomically based, and each month had its own festival. The waxing and waning of the moon determined the monthly cycles and the times for Inca festivals. In his letter to Philip II, Guamán Poma de Ayala offered two different versions of Andean religion, one centering on state ceremonies at Cuzco and the other describing the agricultural practices at the local level. Different calendars prevailed on the irrigated coast, where the agricultural cycle has a different schedule.

HISTORIC PERIOD

Pope Alexander VI conceded the right to conquer half the world each to the royal families of Spain and Portugal on the condition that the conquered peoples would be converted to Christianity. The Hispanic conquest of the Incas enforced new religious traditions in the area. The Andean people replaced Inca state religion with the Catholic state religion under threat of death to those who failed to profess their faith in Catholicism.  The church inquisitors paraded heretics in dunce caps at public autos de fé before burning them to death at the stake. A 'Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición' functioned in Lima from 1569 to 1820. The Spanish indoctrinated the Indians and imposed Roman Catholicism, forced them to build many thousands of churches, and substituted fiestas for patron saints in each village. The conquerors had even forced the Indians to abandon their previous custom of living dispersed amid their fields. Villages were seen as a way of controlling the population, including enforcing their conversion. The people were not entirely converted, however. The spiritual practices of respect for and propitiatory rituals to the Sun and Mother Earth as Creators of all life continued, albeit out of sight of the Spanish clerics. The church inquisitors paraded heretics in dunce caps at public autos de fé before burning them to death at the stake. A 'Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición' functioned in Lima from 1569 to 1820. The Spanish indoctrinated the Indians and imposed Roman Catholicism, forced them to build many thousands of churches, and substituted fiestas for patron saints in each village. The conquerors had even forced the Indians to abandon their previous custom of living dispersed amid their fields. Villages were seen as a way of controlling the population, including enforcing their conversion. The people were not entirely converted, however. The spiritual practices of respect for and propitiatory rituals to the Sun and Mother Earth as Creators of all life continued, albeit out of sight of the Spanish clerics.

On August 20, 1822, South American liberator General Jose de San Martin, speaking in the former Inquisition building in Lima, stated, "Peruvians, from this moment the sovereign Congress is installed and the People resume supreme power in all areas." (my translation) The modern political constitution provides for freedom of religion. The Andean people have mixed many prehistoric beliefs into the Roman Catholic rituals to produce a syncretic religion rich in traditions. Today many Andean people are nominally Roman Catholic. In traditional communities the Virgin Mary is associated with Mother Earth, and the terms Virgin and Pacha Mama are interchangeable. Protestant sects have proliferated during the 20th century.

CONTEMPORARY PRACTICES

Festivals and religion are inextricably linked in the Andean region. The role of music and dance in traditional festivals and ceremonies continues to this day. Max Peter Baumann, writing in Cosmología y Música en los Andes, reports as follows: In the Central Andean Highlands, music, dance, song, and ritual are closely intertwined. Dance is present in almost all group-oriented forms of music making. The Quechua term taki (song) does not contain the idea of language that is sung, but also rhythmic melody and dance. The three key terms, takiy ("to sing"), tukay to play, and tusuy ("to dance"), each emphasize only one aspect of the musical behavior of the whole. These three elements are complementary to one another and signify the inherent unity of structured sound, movement, and symbolic expression."

"Musical behavior is always embedded in a particular context within the ritually and religiously oriented cycle of the year, Music making and singing are determined by the agricultural cycle of the two halves of the year, the rainy season (when the seed is sown and the harvest is brought in) and the dry season (when the earth is tended and ploughed). The seasons also determine in general the kinds of musical instruments, melodies and dances that should be preformed. Numerous festivals are celebrated for the deities belonging to the earth. During these festivals offerings are made of smoke, drink and animal sacrifices when the ground is tilled, the seeds are sown, as the plants grow, and as the people pray for a rich harvest. Each celebration has its own set of melodies (wirsus or tonadas) and its own musical instruments. Music and dance are, on the one hand, expressions of joy and at the same time offerings to honor Father and Mother Earth (Pachatata and Pachamama)." (Baumann, p. 19)

Music, dance groups and dance costume are an important part of Andean life today. This author's impression while working in the Azangaro area (Departamento de Puno, Perú) is that every Indian was involved and participated. Celebrations were a common sight in the countryside. Dance in combination with its costumes and music, is the most impressive aspect of folklore in the Altiplano. From village to village and from community to community, choreography, music and costume vary. No two dance groups (eight or more dancers) are quite identical. At regional festivals the most impressive array of these groups represent their villages, producing brilliant spectacles of movement, color and music. This aspect of Andean life draws tourist from the world over to the Altiplano, especially so in Puno. Quechua and Aymara peoples today continue to view nature as very animate. The veneration of Pacha Mama survives. At most major agricultural occasions, such as the initiation of planting or harvest, at the inception of a community event such as a hunt and at other activities of interaction with Pacha Mama, offerings such as drink and coca leaves are first made. This propitiatory action is often combined with recognition of Inti. When this author has participated in these offerings they have been made in the direction of the Sun. Mountains also continue to be venerated as providers of water and respected for their role in determining weather. Occasional ritual intoxication is another feature of Andean culture that the clerics were unsuccessfully in eradicating. The centuries of Spanish attempts to extricate customs viewed as idolatrous has had little effect in the countryside or in the most traditional sectors of modern Andean society. In this author's view this is due to the close parallels between the metaphors of traditional Andean religion and the empirical universe.

See Bibliography page for citations.m Other Andes academic papers:

TUPAC AMARU, THE LIFE, TIMES, AND EXECUTION OF THE LAST INCA EARLY MONUMENTAL ARCHITECTURE OF THE PERUVIAN COAST CHAVIN AND THE ORIGINS OF ANDEAN CIVILIZATION |